Measurement, and the Many Meanings of Happiness Around the World

Economists and psychologists offer differing opinions on how best to quantify a country’s happiness. Reports and rankings from happiness economics are as varied as they are thought-provoking. Our article this month provides an overview of the many measures of happiness across nations.

EMOTION SCIENCE ARTICLESNEW ARTICLES

The equal rights of man, and the happiness of every individual, are now acknowledged to be the only legitimate objects of government.

Thomas Jefferson

Happier People, but Not Necessarily Happier Countries

More than 40 years ago, the economist Richard Easterlin uncovered a counterintuitive association between a country’s wealth with its happiness. Named after him, the Easterlin paradox shows that when people’s incomes rise, their happiness rises as well – but the same trend is not observed when comparing across countries [1]. Richer people are happier, but this does not mean that richer countries tend to be happier over time. Higher Gross Domestic Product (GDP; the total value of all goods and services produced in a country), is often used as a measure of a country’s economic prosperity. But GDP is, at best, an inconsistent predictor of happiness. Economic health is part of, but not the full explanation for a country’s psychological wealth [2]. Since the early 20th century, new indices have been introduced to rank happiness across countries. These rankings are as varied as they are interesting, offering insights to policy-makers on how best to enhance the life satisfaction and well-being of their country’s citizens. But no two national-level happiness indices are identical. Each comprises a range of factors that have been shown by research to be correlated with happiness and well-being. Which measure is best? Take a look and form your conclusions:

The World Happiness Report (WHR)

Probably the most popular measure of happiness across nations, the World Happiness Report (WHR) is a collaboration between Gallup, The Oxford Wellbeing Research Center, The UN Sustainable Development Solutions Board, and the WHR editorial board [3]. The WHR bases its rankings of happiness by asking participants to imagine their best possible life using a measure called the Cantril Ladder. If you were invited to respond to the WHR survey, you would be asked to imagine a ladder comprising 10 rungs and to indicate which rung you are on, with 0 indicating the worst possible life and 10 being your best possible life. The report then uses data on six criteria to explain the difference in these happiness rankings:

References

[1] Easterlin, R. A., & O’Connor, K. J. (2022). The Easterlin paradox. In Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics (pp. 1-25). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[2] Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

[3] The World Happiness Report: About. https://worldhappiness.report/about/

[4] Samuel, S. (2024). One big problem with how we rank countries by happiness. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/24112787/world-happiness-report-country-rankings

[5] Nilsson, A. H., Eichstaedt, J. C., Lomas, T., Schwartz, A., & Kjell, O. (2024). The Cantril Ladder elicits thoughts about power and wealth. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52939-y

[6] Legatum institute (2024). What is prosperity? https://www.prosperity.com/about-prosperity/what-prosperity

[7] Legatum Institute (2024). The Legatum Prosperity Index 2023. https://www.prosperity.com/rankings

[8] Ipsos (2024). Global happiness 2024. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2024-03/Ipsos-happinessindex2024.pdf

[9] Better life index (2024). What’s the better life index? https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/about/better-life-initiative/#question1

[10] Mizobuchi, H. (2014). Measuring world better life frontier: A composite indicator for OECD better life index. Social Indicators Research, 118, 987-1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0457-x

[11] Balestra, C., Boarini, R., & Tosetto, E. (2018). What matters most to people? Evidence from the OECD Better Life Index users’ responses. Social Indicators Research, 136, 907-930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1538-4

[12] Gross national happiness (n.d.). https://ophi.org.uk/gross-national-happiness

[13] Tobgay, T., Dophu, U., Torres, C. E., & Na-Bangchang, K. (2011). Health and Gross National Happiness: Review of current status in Bhutan. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 293-298.

[14] Lepeley, M. T. (2017). Bhutan’s gross national happiness: An approach to human centred sustainable development. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 4(2), 174-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093717731634

[15] The Straits Times (2024). Bhutan to vote as economic strife hits ‘national happiness.’ https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/bhutan-to-vote-as-economic-strife-hits-national-happiness

The happiest countries, from the 2024 WHR are Finland, Denmark, and Sweden, while the unhappiest countries are Lesotho, Lebanon, and Afghanistan. Malaysia ranks 59th out of 143 countries, while our regional neighbours – Vietnam (54th), The Philippines (53rd), and Singapore (30th) outrank higher than us. The measurement of happiness – by using the single-item Cantril measure, however, has been criticized. The measure might be a better indicator of relative status instead of happiness [4]. One study showed that when asked to think about their position on the imaginary ladder, the measure instead prompted people to think about power and wealth – not happiness or well-being [5].

The Prosperity Index

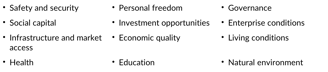

The Prosperity Index is a project headed by The Legatum Institute – a UK-based think tank part of Legatum Limited – a private investment company. Like the WHR, the Prosperity Index also recognizes the limitations of measuring a country’s happiness using economic indicators such as GDP. Instead of happiness, the Legatum Institute proposes the concept of prosperity to better capture how well a country and its citizens are. Prosperity is more than just wealth. A prosperous society is one where people have the freedom to thrive, are part of an inclusive society that protects their freedom and security and can contribute their talents to power a strong and open economy [6]. Prosperity, thus, comprises inclusive societies, open economies, and empowered people. The Index lists the 12 pillars of prosperity under each of these domains:

The 2023 ranking of these pillars ranks Denmark, Sweden, and Norway as the most prosperous countries. Malaysia comes in 43rd out of a list of 167 countries, faring better than Thailand (64th), Indonesia (63rd), Vietnam (73rd) and The Philippines (84th), but being outranked by neighbours Singapore (17th) on this index [7]. Because the Prosperity Index assesses prosperity based on context and environment, the scores can be claimed to be a more ‘objective’ depiction of well-being. But wouldn’t subjective indicators of well-being and happiness also be as important? When market research company Ipsos conducted a 30-country survey of happiness for their recent Global Happiness 2024 report, assessing more subjective measures – family and friends, school, work and quality of life, and well-being, Malaysia (8th) outranked Singapore (11th), but we were less happy than Thailand (6th) and Indonesia (3rd) [8]. We may not be the richest country in the region, but interestingly, we report ourselves to be happier than our more economically prosperous neighbour just south of the border…

The OECD Better Life Index

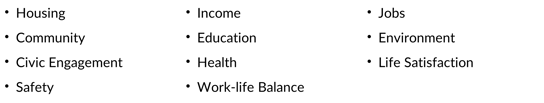

Don’t buy into any of these rankings? You’re in luck. The Better Life Index assesses the well-being of 38 member countries from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), along with some emerging economies [9]. While it covers a small subgroup of countries, this measure is unique in two ways. First, it assesses respondents’ views on which of the 11 areas are most important to well-being – it measures which aspects of well-being are prioritized by a country’s citizens. Second, and as a result of the index’s measure, the Better Life Index does not rank countries – there is no ‘Number 1’ or ‘happiest’ country. Unlike the WHR or Prosperity Index, the Better Life Index does not offer a rankings report or publication to detail the results. Instead, the score reflects what respondents from each country think is important for a better life. The 11 areas priority areas presented on this Index are:

Since no ranking is offered, there’s only so much that we can glean from these results. If decision-makers needed to use the data to shape policy, they would need to take additional steps toward aggregating the data from the index [10]. One study showed that, for some OECD countries, citizens prioritized health, education, and life satisfaction [11]. At the time of writing, a modest sample of Malaysians (n = 445) have responded to the survey indicating that life satisfaction (how satisfied they are with life as a whole), health, and income are priorities for a better life.

Gross National Happiness (GNH)

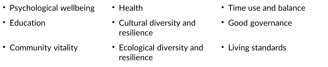

The term Gross National Happiness (GNH) was first coined by King Jigme Singye Wangchuk in 1972, then the 4th King of Bhutan, who proposed the need for a new measure that overcomes the inherent limitations of GDP [12]. GNH has been used to guide the country’s policies and governance in enhancing societal happiness. From this measure, a respondent is classified as ‘happy’ if they meet a 66% cutoff to a series of measures across 9 dimensions. The 9 dimensions of GNH are:

To date, there have been a handful of studies [13] and reviews of Bhutan’s measure [14], most offering praise of the concept and the country’s efforts in emphasizing policies aimed at increasing its citizens’ happiness. Like the Better Life Index, the GNH has not been used to rank happiness across countries for comparison purposes. And, curiously missing from the GNH is any measure of economic prosperity, overlooking any indicator of how economic factors contribute to Bhutan’s happiness. This measure of well-being has also attracted criticism for prioritizing happiness over economic growth and stability. As a result, high rates of unemployment and sluggish economic growth became issues of concern during the country’s last election in early 2024 [15].

What Gets Measured Gets Meaning – and Perhaps, Managed

The measures used to capture happiness each return different rankings and recommendations for government leaders and policymakers. The assessment of a concept of happiness – sometimes nebulous, almost always abstract, and inherently subjective, remains a fascinating science. What gets measured, as it is often said, gets managed. In the case of a country’s happiness, what gets measured has important implications for what governments do for the betterment of its citizens.